In today’s schools, emotional intelligence (EI) is increasingly spoken about on a par with maths and reading. And for good reason: research shows that a high level of EI helps children learn more effectively, build better relationships, cope with stress, and achieve greater success in their future careers and personal lives.

Emotional intelligence is the ability to notice, understand, and manage both one’s own emotions and those of others. The good news is that it can — and should — be developed, and much of this work can be done at home by parents together with their children.

Below are simple yet effective exercises suitable for children of different ages (from 5 to 15 years). It’s best to practise them regularly, for 10–15 minutes a day, in a form that suits the child’s age.

1. “Name the Emotion” (5–8 years)

Aim: To learn to recognise and name feelings.

How to do it: Use cards or simply pictures of faces (you can print or draw them). Show your child one at a time and ask: “What mood is this boy/girl in? Why do you think so?” Then ask the child to act out joy, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, or disgust themselves. Take photos or record a video — children usually love it when gadgets are involved.

A slightly harder version (8+): Discuss why a person might feel two emotions at once (e.g., joy and fear before their first parachute jump).

2. “Emotion Diary” (8–15 years)

Aim: To track one’s emotions and their triggers.

How to do it: Each evening for 3–5 minutes, the child writes down or tells you:

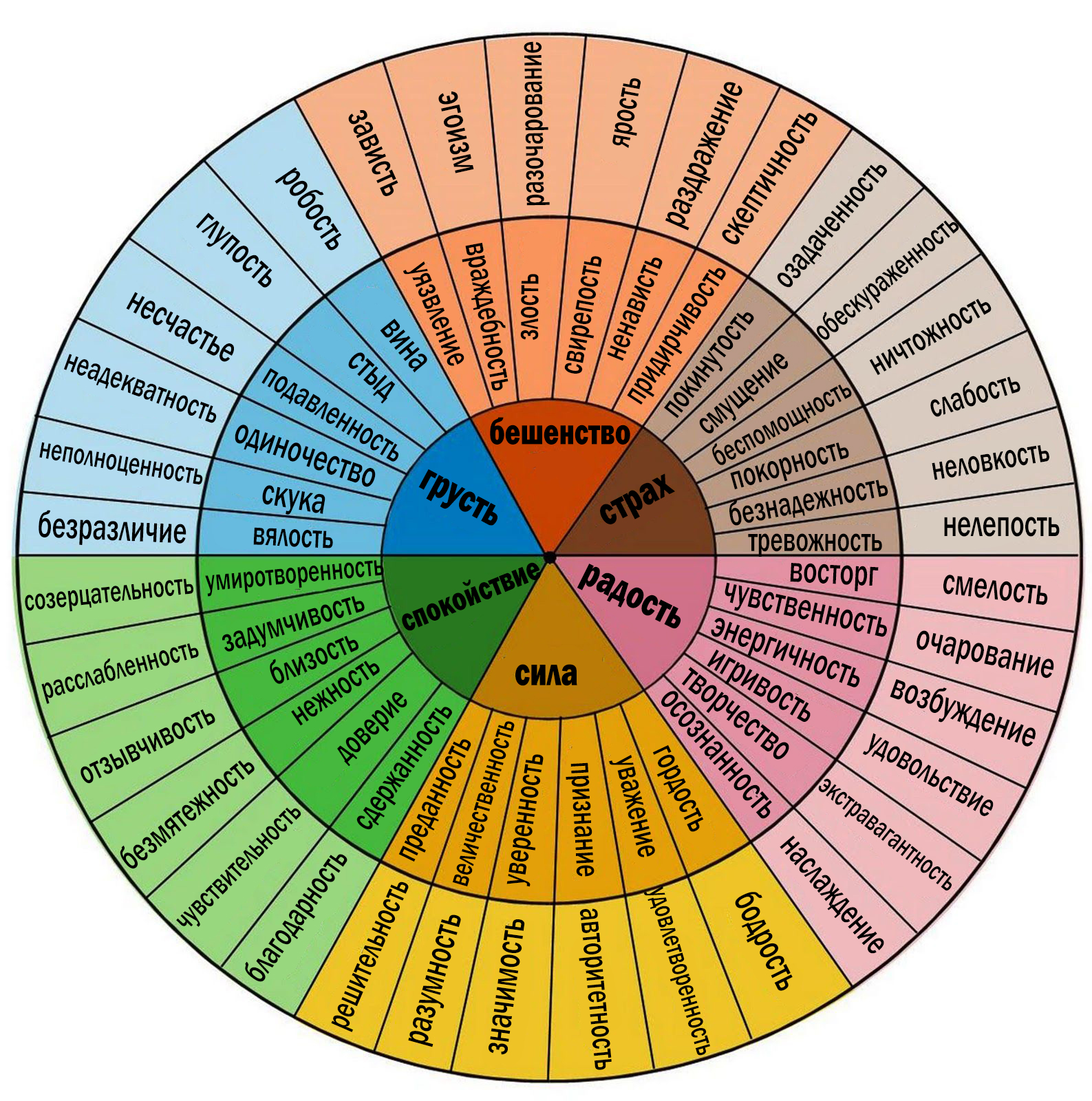

- What did I feel today? (a “wheel of emotions” chart can help)

- What caused these feelings?

- What did I do when I felt that way?

- What could I have done differently?

If you’d like to go digital, voice notes work brilliantly.

3. “Freeze Frame” (6–12 years)

Aim: To learn to manage impulses.

How to do it: When your child starts to get angry or upset, suggest the “Freeze Frame” game:

- Freeze, as if someone has just taken your photo.

- Take three deep breaths in and out.

- Name your emotion out loud.

- Say what you will do next.

Over time, the child will start doing this independently and will be able to control sudden emotions and think through their behaviour in advance.

4. “Anger Letter” (9–15 years)

Aim: To release strong emotions safely.

How to do it: When your child is very angry, suggest writing a letter to the person who upset them (a teacher, friend, sibling). They can write anything they like, even “rude” words. The key rule: no one will read the letter, and afterwards it can be torn up or burned (under supervision). This works remarkably well for relieving tension.

5. “Empathy at Dinner” (any age)

Aim: To understand the feelings of others.

How to do it: At dinner, everyone takes turns saying: “What was the best thing and the hardest thing that happened to you today?” The rest of the family listens attentively and reflects back: “I heard that you felt sad/happy/upset because… Did I understand that correctly?”

6. “Gratitude Jar” (5–15 years)

Aim: To develop positive thinking and notice the good things.

How to do it: Place a pretty jar in the kitchen. Every evening, each family member writes on a slip of paper something they are grateful for that day (even small things: “the sun was shining”, “Mum gave me a hug”, “I solved a tricky problem”). At the end of the week or month, read them together — it’s a powerful boost of warmth and support.

7. “Mirror” (7–13 years)

Aim: To understand non-verbal cues.

How to do it: Take turns showing an emotion using only facial expressions and gestures (no words); the other guesses. Then swap. To make it harder, act out more complex feelings — “I’m tired but I enjoy talking to you” or “I’m angry but I still love you”.

Why it works

All these exercises are built around the four core components of emotional intelligence according to Daniel Goleman’s model:

- Self-awareness (knowing what I feel)

- Self-regulation (being able to manage it)

- Motivation (seeing the purpose)

- Empathy and social skills (understanding others and building relationships)

When parents join in and openly talk about their own emotions (“I felt upset just now because…”, “It makes me happy when you…”), children learn faster and trust the process more.

It’s never too late to start. Even 10 minutes a day spent mindfully talking about feelings will achieve far more than hours of lecturing. Emotional intelligence isn’t just a “soft skill”. It is the foundation of a happy and successful life. And the greatest gift we can give our children is to help them develop it.